CULTURAL SERVINGS:

EPHEMERAL ECHOES

EDWARDIAN PURSE

SCRIMSHAW AND LOVE TOKENS

PILCHARDS AND TROYL

BELTS

LEATHER TANNING

BEER TIME

BEER MATS

LUNCH BOX

SLOW MOVEMENT

SUMMER HEAT

NATURAL DYES

FRAKTUR ART

THE CRIES OF LONDON

SHAKER FURNITURE

BAUHAUS BRUTALISM

BAUHAUS INTERIOR

BAUHAUS SPIRIT

BAUHAUS HISTORY

ROMANTICISM AND REVIVAL

HISTORY OF THE MUSEUM

CABINETS OF CURIOSITY

ROMANTICISM AND REVIVAL

THE STORY OF WILLIAM HARNETT

William Harnett (1848 - 1892) was a painter famous for his ‘Trompe L’oeil’ works in the late 1800s. Exploiting the fallibility of human perception, the trompe l’oeil painter depicts objects in accordance with a set of rules unique to the genre. For example, Harnett represented the objects in his paintings at their actual size, with the objects rarely cut off by the edge of the painting, as this would give a visual cue to the viewer that the depiction was not real. The main technical device, was to arrange the subject matter in a shallow space, using the shadow of the objects to suggest depth without the eye seeing actual depth. Thus the term trompe l’oeil—”fool the eye”. Harnett’s pieces enthral the viewer with a disturbing but pleasant sense of confusion.

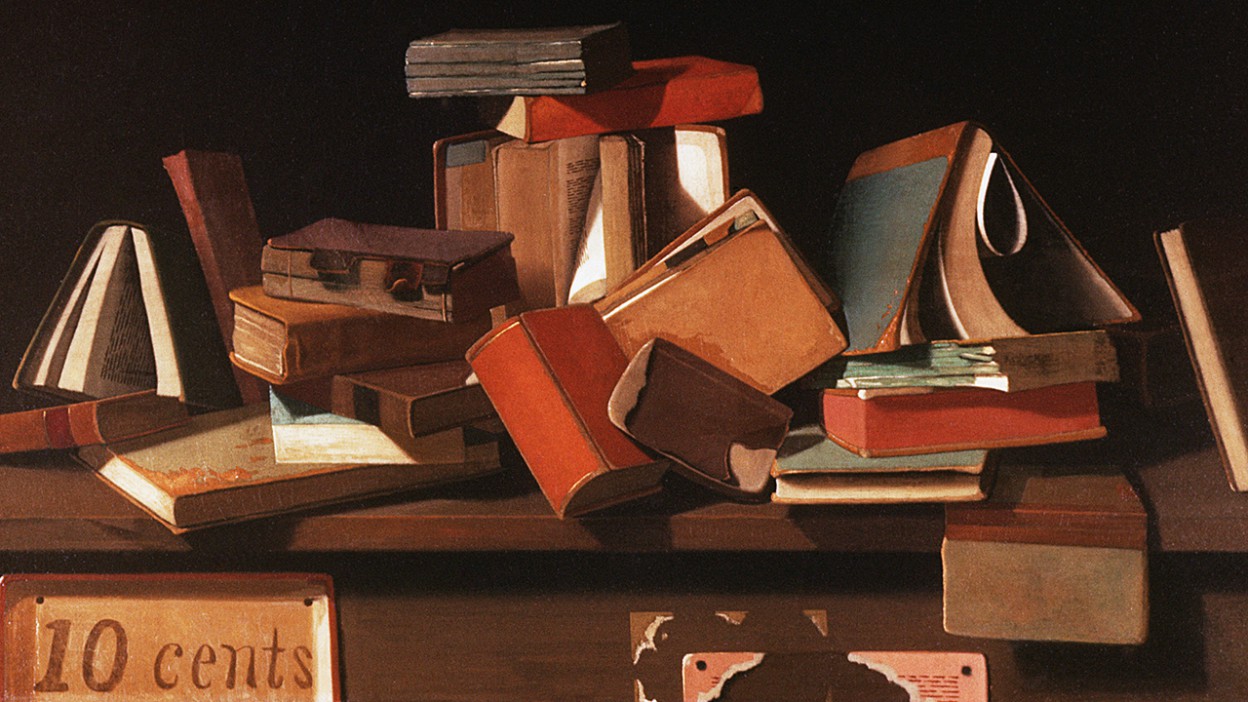

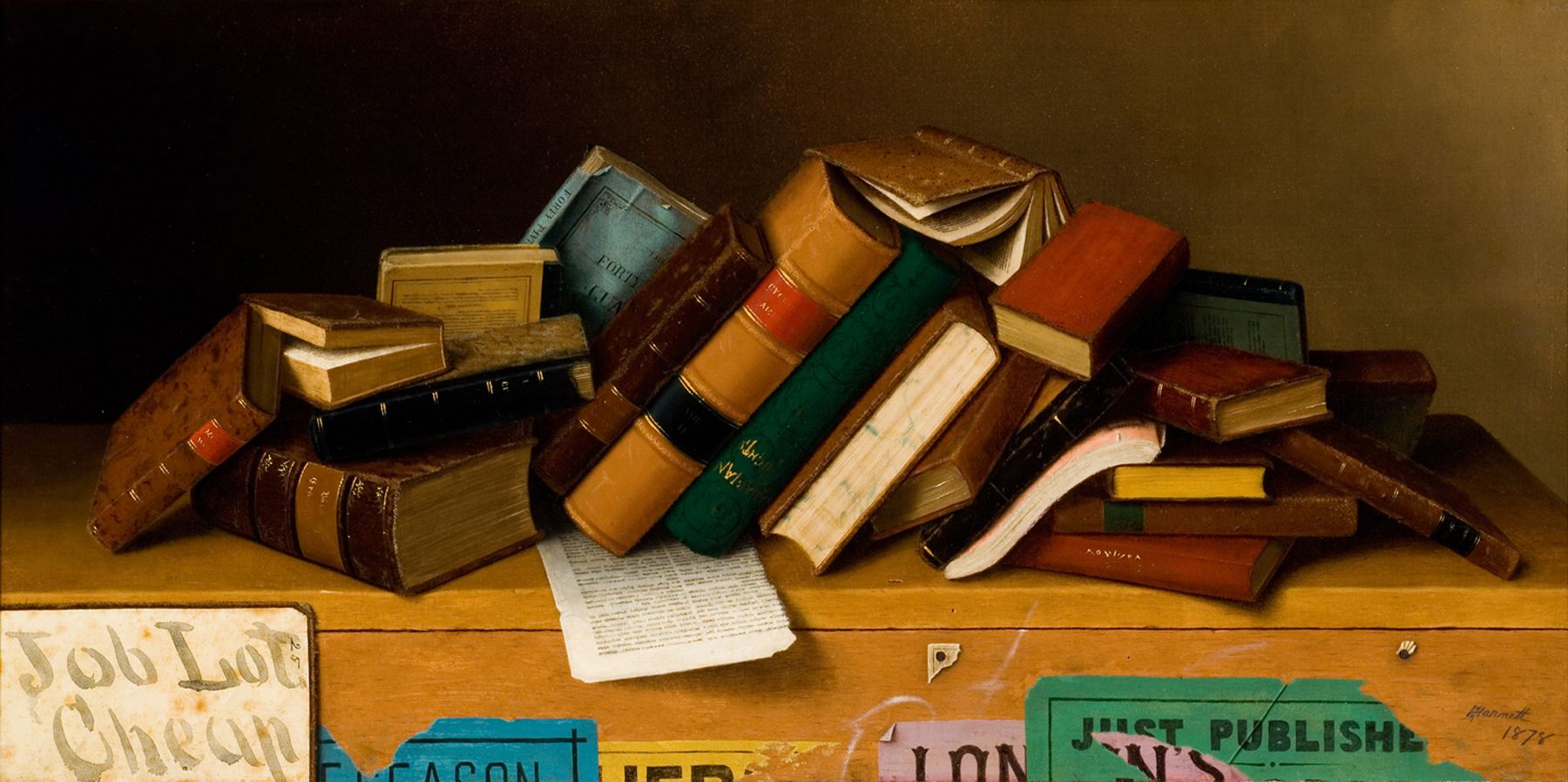

What sets Harnett’s work apart from the many other Trompe L’Oeil painters, besides his enormous skill, is his interest in depicting objects not usually made the subject of a painting. Harnett painted musical instruments, hanging game, and tankards, but also painted the unconventional Golden Horseshoe (1886), a single rusted horseshoe shown nailed to a board, a casual jumble of second-hand books set on top of a crate, Job Lot, Cheap (1878), as well as firearms and even paper currency. His works sold well, but they were more likely to be found hanging in a tavern or a business office than in a museum, as they did not conform to contemporary notions of high art.

Harnett was a successful artist up until he died in 1892. It wasn’t until 50 years later, in the 1940s that his work was rediscovered and brought back to the public eye. Little was known of Harnett, despite the fact that his paintings had started to crop up all over America. Critic Alfred Frankenstien was fascinated by Harnett’s work and took it upon himself to find out more about this mysterious artist.

During his study of Harnett’s work, Frankenstein noticed that some pieces took on a slightly different form to the rest. They seemed slightly more abstracted, with messier brush strokes and a lack of detail. Could these pieces have been mistaken for Harnett’s work? Or could they be forgeries? Frankenstein noted three crucial details which led him to question the authenticity of Harnett’s work. Firstly, about a quarter of his paintings were a different style to the rest, and both styles were practised interchangeably throughout his career. Secondly, whilst he had signed every piece of work, he failed to affix dates to some pieces. And lastly, he had dated two paintings after his death.

Frankenstein broke Harnett’s two styles of painting into the Hard Style and the Soft Style. Hard Style paintings existed with a meticulous attention to detail that was almost microscopic. The paintings were so detailed that specks of sawdust were evident on table tops. Each individual page of a book was indicated; their titles written word for word. Harnett’s Hard Style works were certainly the most eminent of ‘Trompe L’oeil’ as they were so fabulously in-depth that they seemed like real life.

The Soft Style was quite different. The detail was never microscopic, pages were undefined and books existed without titles, the colour was more vibrant, giving the paintings a more abstracted edge. Though the Soft paintings still carried well, with a gorgeous form and subject matter, they seemed nowhere near as visually articulate as the Hard Style paintings.

The two paintings dated after Harnett’s death were incredibly similar, and related more to his Soft Style of painting. Titled ‘Old Scraps’ and ‘Old Reminiscences,’ both paintings depicted letter racks: pieces of leather pinned to a wall with three letters tucked behind. Already suspicious that something was not quite right about Harnett’s paintings, Frankenstein took it upon himself to learn more about the duplicitous style of Harnett’s work, and find out why two of his paintings had been dated after his death.

Whilst examining one of the post-death paintings: ‘Old Scraps’, and with the help of a handwriting expert, Frankenstein was shocked to discover that the handwriting on the three letters in the painting were each written in different styles, none of them baring similarities to Harnett’s own handwriting. Two letters were both addressed to studios that Harnett had worked in, as if to link the piece back to him, and one was written in a script common in most of Harnett’s Soft Style pieces.

Frankenstein took his discoveries to Wolfgang Born, who knew a great deal about 19th Century still life painting and the Trompe L’Oeil movement. Born instructed Frankenstein to investigate the work of John F. Peto, whose own work seemed to resemble Harnett’s Soft Style. Frankenstein visited Peto’s house in New Jersey which his daughter, Mrs. George Smiley, still lived in. The house was filled wall to wall with paintings by Harnett, at least that was what Frankenstein thought at first glance. Peto’s studio was filled with objects that Frankenstien recognised from some of Harnett’s paintings. He had photographs of Harnett’s work divided into two piles, the Soft Style and the Hard Style, and began to link objects in Peto’s studio, to the subject matter of Harnett’s Soft Style paintings. It seemed that almost every piece in Peto’s studio was replicated in one of Harnett’s Soft Style paintings!

Furthermore, the signatures on all of the provable Harnett paintings, whose subject matter did not reside in the studio of Peto, were all discreet and similar. However, the Soft Style signatures were much larger, most of them not even matching each other. It was this discovery that made Frankenstein realise that the paintings mounted on the walls around him were not painted by Harnett, they were Peto’s Soft Style imposters, and that countless pieces by Harnett on display throughout the world were actually pieces by Peto. It is still unknown why Peto signed his pieces as Harnett’s. Perhaps it was to make more money, or it may have been that he wanted to poke fun at the similarities between the entire Trompe L’oeil movement. Either way, it was a rather shocking discovery that some of Harnett’s most celebrated works were painted by someone else.